Triffin Dilemma: The Curse of Reserve Currencies?

Have you ever wondered why the United States dollar plays such a pivotal role in the world economy despite the country being heavily in debt? Or why global financial stability often depends on the decisions made by one country’s central bank? These questions lie at the heart of the Triffin Dilemma, an economic phenomenon that has shaped the global monetary system for over half a century.

In this article, we explore the origins of the Triffin Dilemma, the dual nature of reserve currencies with regard to domestic and international demands, and possible solutions to the dilemma in the future.

What is the Triffin Dilemma?

The Triffin Dilemma, also known as the Triffin Paradox or Reserve Currency Paradox, is the conflict between a nation's need to maintain the stability of its currency by limiting the money supply, and its desire to increase the supply of the same currency to serve as a global reserve currency. This paradox creates a dilemma between short-term domestic economic interests and long-term international objectives.

A good example is the US dollar, the world's reserve currency, which is dominant in international trade and frequently held as a reserve asset by the rest of the world. The demand for dollars as the common trade currency creates a dollar gap, requiring the United States to supply the world with an extra supply of its currency, leading to a potentially ever-increasing trade deficit.

The Triffin Dilemma is named after Belgian-American economist Robert Triffin, an economist who correctly predicted and wrote of the impending doom of the Bretton Woods system in his 1960 book, Gold and the Dollar Crisis: The Future of Convertibility.

How the Triffin Dilemma Came About

The Triffin Dilemma emerged in 1960, when the world economy was grappling with the so-called “dollar gap”. Belgian-American economist Robert Triffin identified the tensions between domestic and international currency requirements that arise when a nation’s currency, such as the US dollar, is adopted as the world’s reserve currency. At the center of this conundrum were the Marshall Plan and the issues surrounding gold convertibility, which together laid the groundwork for the Triffin Dilemma.

The Marshall Plan, a U.S.-sponsored program implemented after World War II, provided assistance in the economic revival of Western European countries and ensured U.S. geopolitical influence in the region. This massive influx of aid and investment, totaling $13.3 billion, stimulated European industrialization and trade between the United States and Europe, increasing the demand and circulation of US dollars. Meanwhile, gold convertibility issues emerged as the U.S. had more dollars in circulation than gold backing them, causing discrepancies in gold prices.

Marshall Plan and Dollar Circulation

The Marshall Plan’s success in reviving European economies and expanding trade relations resulted in a higher demand for U.S. dollars. The U.S. dollar’s newfound prominence as the world’s reserve currency paved the way for a global monetary system that would become increasingly reliant on the dollar for stability and liquidity.

United States secretary of state George C. Marshall

This reliance on the U.S. dollar had consequences for the global economy. During that period, the Bretton Woods System was the international monetary system. The dollar was to be pegged to the value of gold, and the rest of the world's currencies were linked to the dollar. The Bretton Woods System was not a true Gold Standard. Instead, it was a Gold Exchange Standard that was less strict in terms of the dollar-gold relationship.

As the circulation of dollars increased, so too did the demand for gold, which was used to back the value of the dollar at a fixed exchange rate under the Bretton Woods system. This created an imbalance between the supply of dollars and the gold reserves that backed them, ultimately leading to the Gold Exchange Standard becoming unsustainable.

Robert Triffin's Prediction

Robert Triffin, a professor at Yale University, correctly predicted the collapse of the Bretton Woods System in a 1959 Congress' Joint Economic Committee. Triffin observed a fundamental problem in the international monetary system where a dollar glut exists outside of the United States. In order to fuel the world's economic growth, the United States is obliged to supply liquidity to the world with U.S. dollars, which requires the U.S. to continually run balance of payments deficits.

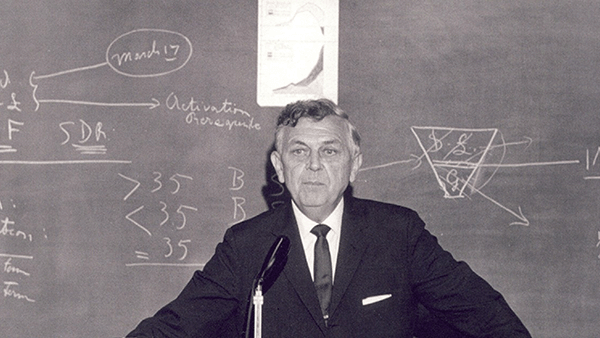

Robert Triffin

However, if U.S. deficits become excessive, they would erode confidence in the dollar's gold convertibility. In addition, the prospect of the United States being unable to maintain a balance of payments surplus would eventually lead to the dollar possibly losing its reserve currency status. A fixed exchange rate system, like the Bretton Woods agreement, would not be able to maintain liquidity and confidence - a dilemma known as the Triffin Dilemma.

Gold Convertibility Issues

As the value of the dollar continued to rise, the U.S. found itself with more dollars in circulation than gold reserves to back them. This discrepancy in gold prices was a ticking time bomb, as it threatened to erode confidence in the dollar and destabilize the international monetary system. The Bretton Woods system, which pegged the U.S. dollar to gold at a rate of $35 per ounce, further exacerbated the problem.

Countries that held dollars began questioning if the United States had sufficient gold reserves to back the currency. Under the Bretton Woods Agreement, central banks were able to redeem U.S. dollars for gold from the United States. Countries like France were concerned about the possibility of dollars that could not be redeemed should there be more circulating dollars than gold, at the fixed price of $35 per ounce.

In an attempt to maintain the fixed exchange rate and honor the convertibility of dollars into gold, the London Gold Pool was established in 1961, and the General Agreements to Borrow (GAB) in 1962. However, these measures were ultimately insufficient, as runs on gold and the devaluation of the pound sterling led to the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971. The end of the Bretton Woods system confirmed the reserve currency paradox, as it highlighted the inherent tensions between domestic and international currency demands.

Creation of the Bretton Woods System in July 1944

The Dual Nature of Reserve Currencies

Reserve currencies, such as the U.S. dollar, have a dual nature that affects both domestic and international economies.

The Triffin Dilemma highlights the delicate balance that must be struck between these two aspects of reserve currencies. As the domestic currency of a reserve country becomes more prominent in the international monetary system, the country’s monetary policy is no longer solely a domestic concern but also an international one, necessitating an equilibrium between domestic economic objectives and international obligations.

Domestic Effects of Reserve Currencies

One of the consequences of having a national currency as a reserve currency is the potential for domestic inflation. This can occur through various mechanisms, such as currency appreciation, an increased money supply, and reliance on external financing. Inflationary pressures can lead to reduced export competitiveness, as a strong domestic currency makes exports more expensive and less competitive in international markets.

Conversely, a reserve currency can offer some advantages for the domestic economy, such as reduced exchange rate risk and increased buying power. However, these benefits come with their own set of drawbacks, such as the accumulation of debt creating asset bubbles, and the weakening of the export industry, resulting in trade deficits and job losses.

International Implications of Reserve Currencies

Reserve currencies also play a crucial role in shaping international economic stability and capital flows. By enabling countries to borrow money more conveniently, reserve currencies can help promote economic growth and stability on a global scale. Furthermore, the accumulation of total foreign exchange reserves by central banks can assist countries in managing economic crises and unforeseen emergencies.

However, in the case of the United States, having a large dollar glut outside of the country presents the possibility of a major currency devaluation should global dependence on the dollar wane when it loses its reserve currency status eventually. Such a scenario is well articulated by Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, who has researched how empires have risen and fallen throughout history, gaining and losing reserve currency status in the process.

Reserve Currencies: An Exorbitant Privilege with a Price

The issuer of a reserve currency enjoys the benefits of being able to use its currency to acquire foreign commodities and products freely. Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, a French finance minister, calls it an "exorbitant privilege" as foreigners see themselves supporting American living standards, allowing them to live beyond their means. Given the dominance of U.S. dollars in international trade, it is difficult for individual countries to move away from the currency even if they resent America's exorbitant privilege.

However, the Triffin Dilemma serves as a reminder that the benefits of reserve currencies come with their own set of challenges. The dilemma underscores the difficulties of maintaining a global reserve currency that is also an international public good and highlights the potential risks when a single currency dominates the international monetary system.

Proposed Solutions to the Triffin Dilemma

Creation of New Reserve Units

Robert Triffin believed the solution to the Triffin Dilemma was the creation of new reserve units, similar to John Maynard Keynes' Bancor proposal. These reserve units would not depend on gold or a reserve currency, allowing the reserve currency issuer to reduce its balance of payments deficits. Global economic expansion would also not be curtailed.

An example of such reserve units is the International Monetary Fund's Special Drawing Rights (SDR), created in 1969. However, the U.S. dollar continues to eclipse SDRs in prominence today, with the latter relegated to being an international reserves supplement, especially in a crisis, and not used as payment in global finance and trade.

Creation of a Modernized Gold Standard

The adoption of a modernized Gold Standard has also been put forth as a solution to the Triffin Dilemma. Jacques Rueff, a prominent French economist, was a strong opponent of Gold Exchange Standards like the Bretton Woods System, calling it a "corrupt" form of the Gold Standard. Rueff assessed that such pseudo-gold standards depended on the dominant currency, not gold.

The failure of the Bretton Woods System in 1971 was the second collapse of Gold Exchange Standards in the 20th century - the first being the Gold Exchange Standard failure in the 1920s where the world also financed the United Kingdom's balance of payments deficits.

Rueff believed that only reinstating the Gold Standard would restore stability to the international monetary system. His proposal requires international currencies to be convertible into gold, and foreign assets of central banks to be confined to gold. A dollar glut would also require the dollar price of gold to be raised, resulting in a devaluation of the currency.

Raising of Interest Rates

Economists have also suggested raising interest rates as a solution to the Triffin Dilemma. Their rationale was to reduce borrowing demand for the dollar, thus narrowing the current account deficit. While sound in theory, this approach is unrealistic as high-interest rates would also mean lower growth in the United States and the world, with the onset of recessions a likely possibility.

In current times, a sustained high interest rate level would also increase the United States' debt-servicing costs, given the multi trillion U.S. Treasury market. Relying on high interest rates to balance Uncle Sam's books would be a long and painful process that would not be politically popular.

The Takeaway

The Triffin Dilemma, highlighting the inherent conflict in the current reserve currency system, where the reserve currency issuer must perpetually run a balance of payments deficit to supply global liquidity, could act as a catalyst for innovation and reform in global financial architecture, steering the world towards a more sustainable and resilient monetary order. Such a shift could foster greater stability, reduce the systemic risks associated with the over-reliance on the US dollar, and encourage international cooperation in managing global liquidity. There are proposals to restore a version of the Classic Gold Standard in the next international monetary system iteration. Perhaps only the world's original money can solve the world's money problem.