The Degradation of Money from the Gold Standard to the Fiat Dollar Standard

Rising inflation is now a global concern. News of protests around the world over the soaring costs of living is rife. The effects of inflation have become real as we face rising prices in our daily lives.

Officials and central bankers are blaming supply chain disruptions caused by the Covid pandemic.

However, a startling pattern of the causes of inflation emerges when we review how the international monetary system has changed since the beginning of the 20th century - from the Classical Gold Standard to the Gold Exchange Standard and, eventually, today’s Fiat Dollar Standard.

When we view today’s problems through history’s lens, we see the unmistakable recurring parallels with the past and understand that the central problem is really currency debasement.

Classical Gold Standard (1870 to 1914)

The Classical Gold Standard was not planned at an international conference. Instead, it came naturally based on many centuries of experience and practice – encountering currency debasement and finding solutions to preserve money's purchasing power.

This international gold standard was a logical treatment of what money ought to be, that it should be a good store of value.

Under the Classical Gold Standard, participating countries (such as the U.S., Canada, Australia, France, and Germany) fixed the value of their country's currency to a specified amount of gold. For example, the United States fixed the price of gold at $20.67 per ounce. Non-participating countries could, in turn, link their currency to that of a country that did so.

Having a Gold Standard does not mean that people have to carry around bags of gold coins. They had the option to use gold-backed paper currency for transactions, and currencies could be converted into gold.

The Gold Standard, as a monetary system, operated with such predictability and was rules-based, strictly limiting the amount of circulating currency to a multiple of central banks' gold reserves.

Countries with a balance of payments deficit would see gold outflows, while countries with surpluses would experience gold inflows. Therefore, it was difficult for a country to have a persistent trade deficit which would lead to persistent net outflows of gold, without potentially destabilizing the currency's value.

While the Gold Standard existed from 1821, the period between 1870 to 1914 is often regarded as its heyday. Currencies' purchasing power was stable, and inflation was only between zero to one percent. The period of the Classical Gold Standard was marked by unprecedented peace, economic growth, and relatively free trade in goods, labor, and capital.

Gold Exchange Standard (1922 to 1931)

When World War I broke out in 1914, many countries went off the Classical Gold Standard to indulge in war financing. Had the Gold Standard not been suspended, the war would not have lasted more than a few months.

Instead, the negligence of monetary discipline with deficit spending and printing paper money resulted in a four-year war that devasted major economies with millions of lives lost.

With the conclusion of the war in 1918, countries began rebuilding their economies, and a return to the Gold Standard was considered. However, it was impossible to return to the pre-war Gold Standard without devaluing currencies, given the war inflation.

Only the United States remained on the Gold Standard during the war.

The global monetary system stayed in limbo until the 1922 Genoa Conference, where all European governments resolved to adopt the Gold Exchange Standard, under which only the United States dollar was as good as gold. Although Britain was not on the Gold Standard, it redeemed pounds not merely in gold, but also in dollars.

European countries bereft of gold as a result of the war could hold pounds as foreign exchange reserves. The result was a pyramiding of the U.S. dollar on gold, British pounds on dollars, and other European currencies on pounds.

Unfortunately, adopting the Gold Exchange Standard was not a return to the Classical Gold Standard. Redemption of gold by European citizens was restricted to large gold bars, which were unsuitable for day-to-day transactions, instead of coins. This prevented an exodus of gold from central bank vaults.

The Gold Exchange Standard created global demand for the dollar and the pound, both of which Great Britain and the United States were glad to print and supply the world.

However, foreign exchange reserves held in European central banks reached levels far higher than the Genoa Conference participants envisioned. In the ten years prior to World War I, European central banks held between $250 million and $400 million in foreign exchange reserves. By 1928, they were $2.5 billion.

Without the restraints of the Classical Gold Standard, Great Britain and the United States printed much more currency than gold in their reserves. Both currencies were overvalued, and both countries had a chronic balance of payments deficit.

Between mid-1922 and 1928, bank credit expanded by over twice as much as the financing for World War I. On the surface, there was great prosperity during the Roaring Twenties, and people became affluent. In reality, inflation was rife, and money went into the stock market and real estate, causing speculative excess. The Dow Jones Industrial Average increased six-fold between 1921 and 1929.

By 1928, the Federal Reserve began tightening liquidity by raising interest rates. This act was followed by foreign central banks. Bereft of liquidity, the epic U.S. boom ended in the cataclysmic Wall Street Crash of 1929. Similar financial crashes followed in Europe and other parts of the world, heralding the beginning of a depression.

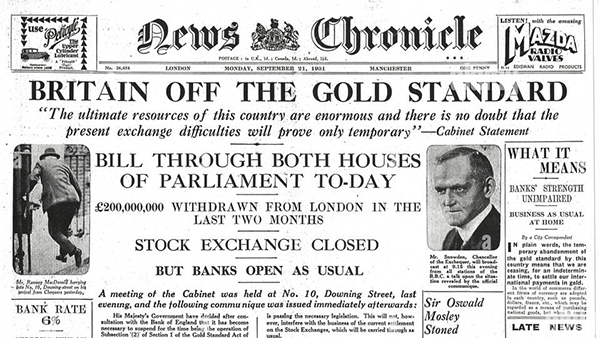

With confidence evaporating in the financial markets, countries like France, holding pounds in reserves, began asking Great Britain for gold. Runs on British gold eventually forced Great Britain off the Gold Standard in 1931.

This development stunned the world as Great Britain was viewed as the world’s premier financial power for centuries. It brought about the collapse of the Gold Exchange Standard and turned an economic depression into the 1930s Great Depression.

Britain goes off Gold Standard in 1931 (Source: Alamy)

Bretton Woods System (1944 to 1971)

The Bretton Woods System that emerged post-World War II was not a Gold Standard. Instead, it was similar to the Gold Exchange Standard of the 1920s. The dollar was fixed to gold at $35 an ounce, and other currencies were pegged to the dollar.

Like the Gold Exchange Standard, the Bretton Woods system contained within itself the seeds of its own destruction because gold was not the arbiter of trust. Instead, it was faith that the U.S. government would ensure that the dollar was as good as gold for trade.

Once again, like its 1920s predecessor, the Bretton Woods system gave the United States the power to print currency and run a balance of payments deficit.

Seeing similarities with the 1920s, Jacques Rueff, a prominent French economist and adviser to the French government, predicted the eventual Bretton Woods system collapse in a 1965 interview with The Economist.

In Rueff’s view, dollars, being the reserve currency, accumulated with foreign central banks in trade with the U.S. Since the dollars are “of no use in Bonn, or in Tokyo, or in Paris,” the dollars are re-lent to the U.S. money market the very same day, the place of dollar origin.

Therefore, the U.S. “never feels the effect of a deficit in its balance of payments.”

Rueff further illustrates with an example: “if I had an agreement with my tailor that whatever money I pay him he returns to me the very same day as a loan, I would have no objection at all to ordering more suits from him.”

As dollars began piling up in foreign central banks’ reserves, there were increasing doubts about whether dollars were really backed by U.S. gold reserves. Inflation had risen from 1.5% in 1960 to nearly 6% in 1970.

Runs on U.S. gold followed, first by private individuals redeeming dollars for gold and then by foreign central banks. In a desperate attempt to stem the outward flow of gold, President Nixon announced closing the gold window in 1971, thereby severing the dollar's link to gold.

Fiat Dollar Standard (1971 - Current)

The Nixon Shock of 1971 was the primary catalyst for the 1970s stagflation, which saw double-digit annual inflation occur twice within a decade, reaching a high of nearly 14% in 1980.

Floating world currencies have been anything but stable since. Despite being the dominant reserve currency, the U.S. dollar has lost at least 87% of its purchasing power since 1970.

It is no wonder why the gold price has risen from $35 per troy ounce in 1971 to as high $2,074 per troy ounce in 2020 - more and more dollars are needed to buy the same ounce of gold.

Without the need for any gold backing, the U.S. kept expanding the domestic money supply by printing the US dollar (Federal Reserve notes) and the national debt has ballooned to over $31 trillion dollars with a perennial widening balance of payments deficit.

Every economic recession or crisis has been met with new waves of money printing by the Federal Reserve. With huge increases in the money supply, more paper money has seeped into the economy chasing the relatively similar quantity of goods and services.

This overissuance of fiat currency is the primary cause of the high inflation that we are experiencing now.

It is time we realize that there is little to no precedent of the U.S. government repaying its debt fully since the country’s inception. Instead, debt default is the likely scenario, given the many instances in history.

A Clear Repeating Pattern of the Monetary System's Degradation

We can see a clear pattern of the degradation of the monetary system and currencies as the rigorous Classical Gold Standard gave way to the sub-standard Gold Exchange Standard surrogate, which failed and brought about the full fiat monetary system we are now living under.

With the systematic removal of gold from the international monetary system, governments have never succeeded in reining in real inflation and debt. They have never preserved the purchasing power of currencies. They consistently fail despite politicians’ promises or central bankers’ assurances. Without gold, the original money, currencies will always be debased and cannot survive.

When the current Fiat Dollar Standard implodes, can the monetary system go any lower in its next iteration, or will gold be once again called upon to be its bedrock? There are already signs of the latter. Global central banks have accumulated gold reserves this year at a pace never seen since 1967. This ‘run’ on gold will only accelerate once inflationary pressure proves to be untenable despite the Fed’s actions.

History is rhyming once again if it is not repeating exactly.