The Cost of Dollar Sterilization

Introduction

What does Dollar Sterilization mean?

The best way to explain dollar sterilization is perhaps with a real-life example.

If you lived in America during the early 1990s, you’d head to a K-mart or a Sears for most of your daily needs. These huge chain stores were everywhere and stocked almost everything you could want or need. Then came Walmart, with its efficient logistic systems and a huge supply of cheap goods sourced from China.

Walmart’s supply of cheaper goods created a price advantage, eventually letting it succeed where K-mart and Sears didn’t. But what’s curious about this is how the price of goods sourced from China stayed so low for such a long time, even when quality got better and better. In a normal market, the prices should eventually have increased. So how was that so?

The answer to that is dollar sterilization.

When demand, supply and price don’t move in unison

Dollar sterilization is a way for a government or central bank to control the value of its currency compared to the US dollar. If they feel their currency is getting too strong, they will sell their own currency and buy US dollars.

Conversely, if they feel their currency is getting too weak, they will sell US dollars and buy their own currency.

With trade, money flows to the country that produces, which means the country doing the purchasing is essentially buying the currency of the producer, causing that currency to appreciate.

For example, the increase in US dollar transactions with Walmart should have caused the Chinese Yuan to strengthen over time, leading to a relative increase in the cost of goods from China. But that didn’t happen.

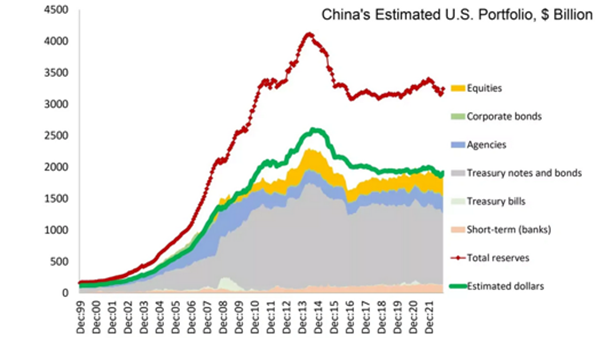

To keep their currency and goods inexpensive, the Chinese government instructed Chinese banks who received US dollar from abroad to turn that US dollar over to Chinese authorities. The authorities then sent the dollars back to the United States, primarily to purchase US Treasury Bonds. That’s a large reason why we see that China’s US portfolio spiked sharply from 2009 to 2013.

By doing so, a large portion of the incoming US dollars were never used to purchase Chinese Yuen. On the other hand, the Chinese government paid their local manufacturers by printing more Chinese Yuan.

So while China eventually experienced domestic inflation as a result of the increased money supply, the exchange rate with the US dollar was kept artificially low for a long period of time. Chinese-made goods thereby remained cheaper for much longer than should have occurred in a free market, artificially lowering inflation in the western world.

Essentially, the Chinese government sterilized the US dollar purchasing effect on the Chinese Yuen. Furthermore, the large purchases of US debt, using these “sterilized” dollars, further amplified the cheap money era of the 2010s.

Unintended effects of Dollar Sterilization

We must remember that just as price and demand for different baskets of goods can change independently, so too, can inflation apply differently.

Going back to the example above, the supply of cheap imported Chinese goods allowed the prices of other US-made goods to rise, because US citizens could afford to spend more on them.

The continued supply of cheap Chinese goods and massive US treasury purchases made money cheap, which indirectly subsidized goods, services and investments that benefit from cheap financing, like real estate, equities, and education. Since inflation was low US central banks kept interest rates low, leading to the creation of easy credit.

Low interest rates meant you could loan more and pay it off cheaply over a longer period. This meant a substantial amount of income was now available on the markets, which was part of the reason why we saw a real estate boom and the stock markets soar.

There is always a cost

The low interest rates and easy money contributed to over-borrowing, with people and institutions taking on debt that they couldn’t necessarily pay off.

What’s more, if something is viewed as a necessary good, demand can hold irrespective of price. That’s why in the case of education for example, rising prices had little effect on demand. Despite enormous tuitions, prospective students were willing to accumulate greater debt burdens, fueled by cheap financing, made possible by low interest rates, made possible by low inflation.

We pay the price for ultra-low interest rates

In the end, a country that produces and exports most of its goods cannot indefinitely keep its currency low versus a country that mostly consumes goods.

By printing vast amounts of currency to keep its exchange rate vs. the US Dollar low, China has ensured the long-term raising of prices of goods priced in yuan at home. Despite efficiency improvements, Chinese-made goods are no longer as cheap as they used to be, and trade wars will only push prices higher.

As more currency chases fewer goods, inflation will likely stay high partially to make up for the low prices from the last decade.

The price of goods is set to rise, and we’ll see a structural increase in inflation. This inflation is not likely to be going away soon. It’s a consequence of the past decade of ultra-low inflation.